In his new solo series, Matthew uses "Life is Strange" to talk about one of gaming's most important mechanics.

Video version is on our Youtube Channel!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=muixLvYHE4M

Hate listening to sound? Text version below:

***contains minor spoilers for Life is Strange, a lovely adventure game I highly recommend playing without spoilers. If you want, go give the first episode a try for free on Steam and then come back!

Choice and consequence has been

one of the defining, unique traits of videogames from the very beginning. In

many games, the choices are presented as possible solutions to a problem:

-Mario needs to get past a

Goomba. How do you do it?

-Missiles are raining down on

your cities! What order do you shoot them down in?

-Asteroids are surrounding your

ship, how should you proceed?

The consequence in most games are

simple: you either succeed or you fail. And they’re usually tied directly to

the execution of your choice. You choose to jump on the Goomba’s head, but if

you miss, Mario’s in trouble. You may choose the right order to shoot at the

missiles, but you need to aim properly. You either clear the asteroids, or you

get smashed to pieces after a poorly timed hyper jump.

In other cases, the gameplay’s choices

and consequences involve more critical thinking. One of my favorite examples of

gameplay choice is in Halo: Combat

Evolved. Thanks to the 2 weapon carry limit, the player is having to

constantly make decisions on what weapons to take with him to the next

encounter. And since the weapons are designed for pretty specific

circumstances, your choice will have major consequences on how your next fight

goes, especially if you’re not sure what types of enemies you’ll encounter.

Do I take the powerful sniper

rifle, despite its limited ammo? Or do I take the scoped pistol, which is much

weaker but more versatile? And what should I combo it with? The plasma pistol

for its charged shot? Or the hot-pink needler for its usefulness against Elites

(assuming you’re on legendary mode. Otherwise DROP THE NEEDLER IT’S TERRIBLE).

Gameplay choice is the most

common version of this mechanic, but today we’ll be focusing on narrative choice.

Narrative choice is a common staple

of RPGs, especially Western RPGs in the post-Knights of the Old Republic era. The player is faced with a

decision that will have lasting effects on the rest of the narrative. Sometimes

it will be a binary “good” or “evil” choice (Fable, KOTOR) sometimes it’ll be a little more nuanced than that (the

Mass Effect series), and sometimes

it’ll be a choice impacting the relationship between the player character and others

(Persona, all the Bioware games).

This aspect of choice and

consequence has always excited me the most, creating narratives that are not

only interacted with, but shaped by the player. This is where, as a form of

expression, video games are wholly unique. And in a time where the Internet has

given us all the ability and desire to create our own content, videogames have

the chance to become our culture’s most beloved artistic medium.

That brings us to Life is Strange, an episodic adventure

with some of the most successful uses of choice and consequence I’ve ever experienced.

The story follows a high school senior girl named Max Caulfield who

discovers that she has the power to rewind time. With this newfound ability,

Max rescues then reunites with her childhood friend Chloe, and together they

try and solve the mystery of what happened to Chloe’s friend Rachel, who went

missing several months ago. Oh, and maybe the apocalypse is happening.

And with that setup, the game

becomes a series of choices and consequences. During a scene, Max will

sometimes have to make a choice, with the game pausing to let you think about

it. In most games, the choice and its consequences are final, barring a

reloaded save file. This can sometimes lead to unexpected (and undesirable)

consequences. I lost count of the number of times I pick a dialogue option in Mass Effect, only to have Commander Shepard

take the conversation in a wildly different direction than I thought she would.

Here’s where Max’s rewind power

comes in. The game gives the player time after nearly every choice (with two

very notable exceptions). to rewind and try again. This way, you can see the

consequences of each choice, and decide which one you’d prefer. After you leave

the area, your choice is final.

This seems problematic at first

glance. If you can play through each choice and see which one’s better, where’s

the stakes?

Well, there often isn’t a

“better” choice. These decisions are tough,

with long-term consequences that are difficult to grapple with.

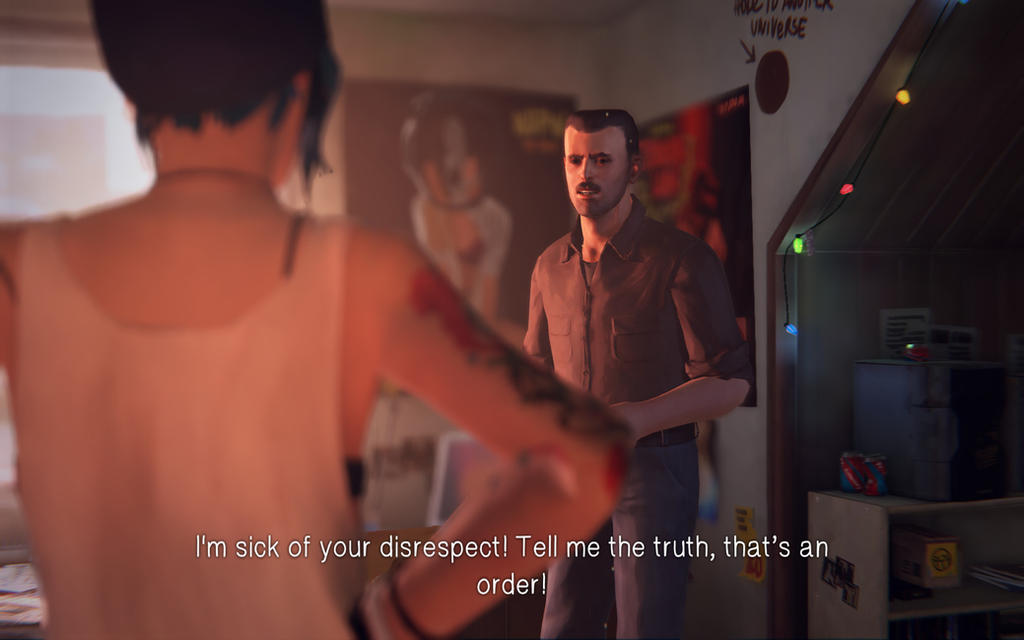

An example: early in the game,

Chloe’s step-father David catches her with weed while you’re hiding in the

closet. Your first choice is to stay hidden. Consequence: Chloe and David get

in a shouting match that culminates with David slapping Chloe. You’ve stayed

out of trouble, but your best friend has endured a terrible experience and

can’t help but be pretty upset with you.

Option 2: Come out of hiding and

take the blame for the weed. Consequence: Chloe is ecstatic that you stood up

for her, but her step-dad is a paranoid security officer who works for your

school. He could make your life a living hell.

There’s not a “right” choice

here. They both have their own pros and cons, and those cons are murky enough

to make predicting their full impact difficult. One confrontation I had in a

later episode resulted in Chloe having to do something extremely traumatic, and it was only possible because of a

particular set of circumstances. Circumstances that I had unknowingly set up

with my choices. I had effectively made my best friend commit a terrible deed

for which she would never forgive herself. It was my fault.

And thanks to the rewind power,

you have all the time in the world to

reflect/stress over these impossible situations. Giving the player that period

of reflection is crucial in these kinds of games.

Think back to PS3 game Heavy Rain. It’s structurally similar to

Life is Strange; you walk your

character around the environment, clicking on objects to hear what the

character thinks about them, and sometimes you have to make choices or take

actions that significantly alter the narrative. But Heavy Rain rarely gave you time to think about your actions. Most

of the scenes that could heavily change the story were basically quick-time

action scenes, where you had to click buttons and wave your controller when

prompted to keep your character alive. There was no time for reflection, no

time to contemplate your situation, only constant panic and hope that the PS3’s

crappy motion controls wouldn’t screw you over.

And the consequences in this type

of adventure game aren’t near as dynamic and interesting. They feel more like a

Mario game; you messed up the button prompt, so your character is dead. Yes,

the narrative is altered, but it feels less like a collaboration between the

player and the game, and more like a punishment for not being good enough at

the game. That’s not the kind of feeling you want to foster in a

narrative-driven game.

Instead, Life is Strange focuses on the nature of the choices themselves,

presenting you with the sort of moral and ethical quandaries that can make you

learn quite a bit about yourself.

What do you think is more

important: your friend’s emotional well-being or the stability of her family?

Is it good to have a gun for your

own protection, or will you just risk escalating a confrontation?

Are you willing to take part in a

loved one’s assisted suicide?

It’s in these moments, the kinds

of decisions I hope I’ll never have to make in real life, that Life is Strange absolutely thrives.

Thankfully, the choices aren’t

always huge, life-changing decisions.

That would get exhausting real quick. Often, the decision is over something

mundane and pretty inconsequential: how much should I water my plant, should I

sign this school petition, what should I have for breakfast? These quieter

choices aren’t highlight material, but they immerse the player in Max’s life

and the Twin Peaks/Juno hybrid world

she lives in. Which is great, because this setting and these characters are

practically unheard of in videogames. How often have you played a game from the

perspective of a teenage girl, in a story centered on the relationship between two

young women?

That relationship is the glue

that ties the game together. Here’s a golden rule to follow for not just

videogames, but all methods of storytelling: consequences have no weight if you

don’t care about the characters they affect. The videogame Fable 2 ends with one of those big “moral decisions” that western

RPGs are so fond of. At the end of the game’s main story, you have to choose

between receiving untold riches, saving the lives of thousands of innocents, or

bringing your recently killed dog back to life.

I have no data to back me up, but

I’ll bet my life that most everyone chose the dog on their first play-through.

The dog is the only character in the game that the player forges a real

emotional connection to. Meanwhile, the innocent people you can save are shallow

caricatures, and money is ridiculously easy to acquire. This isn’t a moral

choice, it’s a no-brainer. The only people who chose the other options were

achievement/trophy hunters or people who hate dogs beyond all reason.

But I deeply cared about Max and

Chloe. For all of its flaws (and there

are many flaws, some of which are just as interesting to discuss as its successes),

the game’s earnest characterization shines through. Even with dialogue that

occasionally sounds like adults pretending to be teenagers, Max and Chloe’s

relationship is authentic, complicated, and beautiful to watch unfold.

I was fully invested in Max’s

increasingly desperate and dangerous attempts to protect her friend. I dearly

wished for Chloe to grow and learn and find some peace in her life. And my

choices as the player could make or break that wish.

This is choice and consequence at

its finest. When done right, it gives videogames an emotional impact that film

and literature could never replicate. Considering that it’s been several days

since I played its final episode and I still

feel like I got punched in the gut, it’s safe to say Life is Strange did right in a lot of ways.

There’s so much more I want to talk

about in regards to this game: its mixed success at tackling some very serious

topics, its unnecessary use of more “game-y” conventions, and of course it’s

devastating and divisive final moments.

For now, thanks for stopping by!

If you’re interested in trying out Life

is Strange, it’s available on PC, Xbox One and PS4, and the first episode

is free. If you have any interest in a videogame’s storytelling potential, it’s

a necessary purchase.